The following is a story I wrote shortly after Steve Tilford’s death. On the one-year anniversary of Steve’s tragic accident, I post it here for the first time to honor his memory. Like every person who had the privilege of meeting Steve, not a week has gone by that a Steve memory hasn’t crossed my mind.

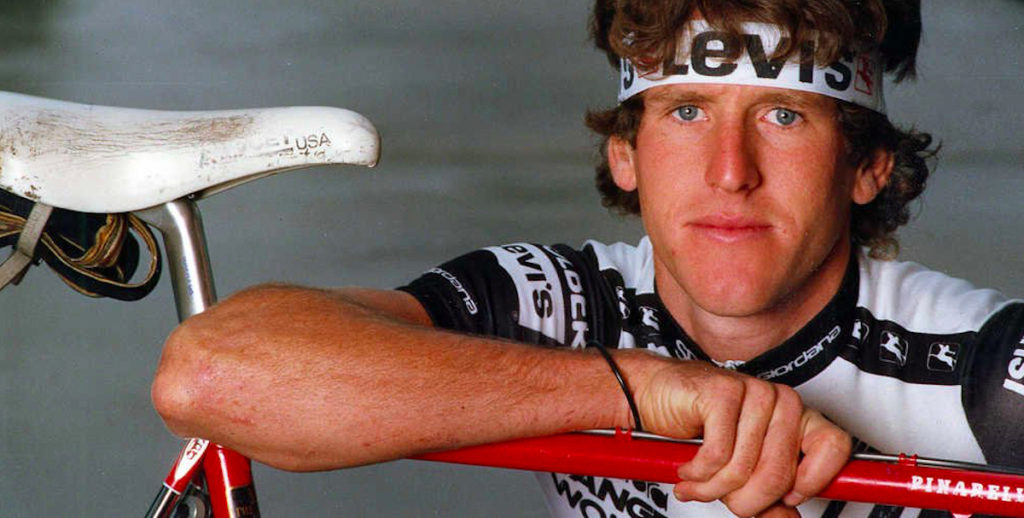

TILFORD TALES: The fast life of a mountain biking legend

Mountain biking lost a beloved friend and champion (both race champion and vocal advocate of mountain biking) on April 5th, 2017 when Steve Tilford was killed in a traffic accident on a Southern Western Utah highway. He was 57 years old. The sudden loss sent shockwaves through the cycling community that reached friends and fans around the globe.

“The news is hard to believe because I’ve seen Steve die at least four times,” said close friend and former teammate Paul Biskup. “There were so many races where Steve was up ahead getting into a situation that would get anybody else killed and somehow he cheated death each time.” A former team manager joked about taking out a life insurance policy on the then 20-year-old Steve Tilford because the manager was sure Steve would meet his end on his bike. Steve proved him wrong.

Steve’s reputation as a risk-taking wildman on the bike is not fair, however. He survived racing bicycles because of superior bike handling skills and being an intensely determined competitor.

INTRO TO MOUNTAIN BIKING

When Steve began racing bikes in his native Topeka, Kansas, in 1975, mountain bikes had yet to be invented. He won the Kansas State Road Championship when he was 14 years old and was named to the United States Junior National Cycling Team in 1978. His superior bike handling skills, mid-western toughness and focused work ethic assured Steve’s success as a cyclo-cross racer. Cyclo-cross was a precursor of mountain biking, where riders compete on an off-road course using modified road bikes. Steve would become a four-time U.S. champion of cyclo-cross.

The announcement of a national championship event for the new sport of mountain biking seemed like a good fit for Tilford. Racing for the Sunk River Cycling team sponsored by Raleigh, Steve was presented with one of three mountain bikes (Alexi Grewal, who would win the Olympic Gold Medal in 1984, and Roy Knickman got the other two). The bikes, crafted by Kent Eriksen, founder of Moots Cycles and today owner of Kent Eriksen Cycles, were painted with the distinctive red/black/yellow Raleigh racing colors. Steve assembled his bike two days before the event, took a shakedown ride and went on to win the 1983 NORBA National Championship. The win sealed Steve’s fate as a lifelong mountain bike racer and advocate for mountain biking.

STEVE’S INFLUENCE

Tilford rode for many trade teams and put together personalized sponsorship programs to fund his racing during a career that, by the way, ended with his death because he never stopped racing.

It was his time racing for Specialized (with Teammates Ned Overend and Todd Wells) that he arguably made his biggest impact on mountain biking. While Steve was not a threat to win a National mountain bike event by this point in his career, he was the master at picking and choosing important regional events.

A rider with Tilford’s reputation showing up at a regional event and racing to the podium made a serious impression on the local riders. This easy-to-approach, enthusiastic rider was a mountain biking ambassador who had few peers (Ned Overend, Dave Wiens and Tinker Juarez are the only other names who come to mind). It was not uncommon for Steve to show up a few days early or stay a few days after an event to ride with locals. There is no doubt that Steve sold a ton of Stumpjumpers during his stint under the Specialized tent.

A SENSE OF FAIRNESS

Why professional mountain bike racers of the 80’s and 90’s didn’t force Tilford into the president’s role of a riders’ union is not a mystery because the young sport didn’t have a riders’ union. If it had and Steve was the president, mountain bike racing would be a stronger sport today. Steve’s mid-western values gave him a clear vision of right and wrong in racing and he wasn’t afraid to let his sense of fairness known to fellow competitors, big-name race team directors or race officials.

When Roland Green took assistance from Ryder Hesjedal at a Big Bear National (caught on video by a TV crew and reported by a number of racers) Tilford protested when officials refused to assess any penalty on Green because “we didn’t see it.” Steve didn’t argue because it would improve his result and he didn’t have a personal grudge against Green. He was protesting because a rule was broken and it wasn’t fair to racers who didn’t break a rule for the action to go unpunished. “If we, as riders, can’t police ourselves, our sport is in jeopardy,” Steve prophetically said at the time. He saw the need to keep an even playing field. It was the right thing to do.

Steve was a vocal opponent of riders using performance-enhancing drugs and was never afraid to call riders out on his popular blog (that contains his heart wrenching last posting from just hours before his death). He viewed drug use as a cancer that had spread through all areas of cycling. He was also optimistic that the disease that could be cured, but not by ignoring the problem or giving riders a pass.

It is amazing that Steve never became bitter at the abuses he detailed in his chosen sport. The only explanation is that his manner of handling these situations was rational, not emotional. He never “hated” a rider for breaking a rule. He simply expected the rider to take the punishment (and in the case of drug use, that meant leaving the sport) and learn from the mistake. Steve had the ability to call riders out and go riding with them later.

THE STORY TELLER

In addition to his racing skills, Steve was a consummate storyteller. “Spellbinding storyteller” is a better description. He could recall specific laps of a race from over 20 years ago. He remembered interactions with other competitors and spectators. He could recall training rides and trips to and from events. And there was no need to embellish a story because Steve lived a life that needed no embellishment.

His storytelling skills and love of an energetic debate are the reasons he was welcomed into homes of even casual acquaintances (Steve was the master of stretching his racing budget by using a gigantic network of willing friends for lodging). Listening to Steve’s stories the night before or the evening after a race could be as interesting or more interesting as the racing itself.

A RACER TO THE END

The Mountain Bike Hall of Fame inductee (Steve was inducted in the year 2000 along with fellow legend Dave Wiens) never stopped racing bikes and had no intention of slowing up. Racing was never a job to Steve; it was a passion that only grew stronger over the years. When Steve lined up for a race, even the casual spectator would see that there was nowhere else he would rather be. In perfect Tilford fashion, he won the last race he entered before he left this mortal coil. He was indeed a racer and rider until the end.

Steve is survived by his longtime partner Trudi Rebsmen (a soigneur with BMC Racing), his brother Kris Tilford and every rider who ever had the pleasure of meeting this true legend of mountain biking.